Goffstown, New Hampshire

Goffstown, New Hampshire | |

|---|---|

Town | |

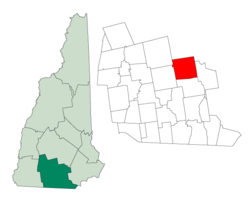

Location in Hillsborough County, New Hampshire | |

| Coordinates: 43°01′13″N 71°36′01″W / 43.02028°N 71.60028°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Hampshire |

| County | Hillsborough |

| Incorporated | 1761 |

| Named for | John Goffe |

| Villages | |

| Government | |

| • Select Board |

|

| • Town Administrator | Derek Horne |

| Area | |

• Total | 37.6 sq mi (97.4 km2) |

| • Land | 37.0 sq mi (95.9 km2) |

| • Water | 0.6 sq mi (1.5 km2) 1.57% |

| Elevation | 308 ft (94 m) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

• Total | 18,577 |

| • Density | 502/sq mi (193.8/km2) |

| Time zone | EST (UTC-05) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-04) |

| ZIP codes | 03045 (Goffstown) 03102 (Manchester) |

| Area code | 603 |

| FIPS code | 33-29860 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0873606 |

| Website | www |

Goffstown is a town in Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 18,577 at the 2020 census.[2] The compact center of town, where 3,366 people resided at the 2020 census, is defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as the Goffstown census-designated place and is located at the junctions of New Hampshire routes 114 and 13. Goffstown also includes the villages of Grasmere and Pinardville. The town is home to Saint Anselm College (and its New Hampshire Institute of Politics), the Goffstown Giant Pumpkin Regatta, and was the location of the New Hampshire State Prison for Women, prior to the prison's relocation to Concord in 2018.

History

[edit]

Prior to the arrival of English colonists, the area had seasonally been inhabited for thousands of years by succeeding cultures of Native Americans; its waterways had numerous fish, and the area had game.[3]

The town was first granted as "Narragansett No. 4" in 1734 by New Hampshire and Massachusetts colonial Governor Jonathan Belcher as a Massachusetts township (the area then being disputed between the two provinces). It was one of seven townships intended for soldiers (or their heirs) who had fought in the "Narragansett War" of 1675, also known as King Philip's War. In 1735, however, some grantees "found it so poor and barren as to be altogether incapable of making settlements," and were instead granted a tract in Greenwich, Massachusetts.

The community would be called "Piscataquog Village" and "Shovestown" before being regranted by Masonian proprietor Governor Benning Wentworth in 1748 to new settlers. These included Rev. Thomas Parker of Dracut and Colonel John Goffe, for whom the town was named. He was for several years a resident of neighboring Bedford, and he was the first judge of probate in the county of Hillsborough. Goffstown was incorporated June 16, 1761.[3] A large part of the town was originally covered with valuable timber. Lumbering and fishing were the main occupations of the early settlers.[3] The village of Grasmere was named for Grasmere, England, home of the poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

A Congregational church was organized about October 30, 1771, and the town made annual small appropriations for preaching. The majority of residents were Congregationalists; residents in the south part were of Scots-Irish descent and were Presbyterian.[3] A meeting-house was erected in 1768; but it was not completed for several years. The first minister was Rev. Joseph Currier, appointed in 1771; he was dismissed August 29, 1774, for intemperance, according to the town records. In 1781, the Congregationalists and the Presbyterians organized separately; the former called Rev. Cornelius Waters, who became their pastor, and continued till 1795. The next minister was Rev. David L. Morril, who began March 3, 1802. He was supported by both congregations under the name of the Congregational Presbyterian church. Morril was elected as a representative of the town to the state house, as a U.S. senator for the state, and in 1824, as governor of the state, serving until 1827.[3]

The Piscataquog River, which bisects the main village of Goffstown and was spanned by a covered bridge, provided water power for industry. In 1817, Goffstown had 20 sawmills, seven grain mills, two textile mills, two carding machines, and a cotton factory. Its textile industry was an example of the economic ties between New England and the American South, which was dependent on slave labor for production of its lucrative cotton commodity crop.

The town was described in 1859 by the following:[3]

The surface is comparatively level, the only elevations of note being two in the southwest part, called by the natives Uncanoonuck. There are considerable tracts of valuable interval[e], as well as extensive plains, which are generally productive. Piscataquog river is the principal stream, which furnishes quite a number of valuable mill privileges. It passes through in a central direction. Large quantities of lumber were formerly floated down this stream to the Merrimack, and the forests at one time supplied a large number of masts for the English navy. The New Hampshire Central Railroad passes through Goffstown. Then; are three villages — Goffstown, Goffstown Centre, and Parker's Mills; three church edifices — Baptist, Congregational, and Methodist; sixteen school districts; and two post-offices — Goffstown and Goffstown Centre: also, four stores, four saw-mills, two grist-mills, and one sash and blind factory. Population, 2,270; valuation, $599,615.

— A History and Description of New England, General and Local

In 1816, the Religious Union society was organized. A new meetinghouse was erected in the west village. Meetings were held two thirds of the time in the new house, and one third in the old house at the center.[3]

In 1818–1819 residents were deeply interested in the preaching of Rev. Abel Manning, as part of the Second Great Awakening. 65 persons joined the church that year. Other ministers were Rev. Benjamin H. Pitman (1820 to 1825), Rev. Henry Wood (1826 to 1831), and Rev. Isaac Willey (1837 to 1853). A Baptist church was formed in 1820.[3]

The town annexed islands on the Amoskeag Falls in the Merrimack River in 1825 and part of New Boston in 1836.[3]

In the early part of 1841, a female commenced preaching here, and shortly more than half the voters in town came into her support. She professed no connection with any church. The excitement created by her preaching, however, soon died out, the result of it being the organization of the existing Methodist church.[3]

The Uncanoonuc Mountains in Goffstown once featured the Uncanoonuc Incline Railway, founded in 1903. It first carried tourists in 1907 to the summit of the south peak, on which was built that year the Uncanoonuc Hotel. The 5+1⁄2-story building provided 37–38 guest rooms, and a dining room that accommodated 120. It also offered outstanding views of the surrounding valley, including Manchester, connected by electric trolley to the railway's base station. The hotel would burn in 1923, and the train was later used to transport skiers to the top. The railway peaked during the 1930s and 1940s, but was essentially abandoned by the 1950s. The summit of the south peak is now the site of numerous television and radio towers.

Grasmere Village straddles the Piscataquog River in the eastern region of Goffstown. The Hillsborough County Railroad Station was located at Grasmere on the southern side of the river. Rail-borne freight for Grasmere and other surrounding locales was delivered to this station during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Another rail station in Goffstown was located to the west closer to the town center, and a third was Parker's Station to the west of the town center.[4]

The railroad line which passed through Goffstown was built by the New Hampshire Central Railroad and was later acquired by the Boston & Maine Railroad in 1895, who operated it as their North Weare Branch. 16.4 miles (26.4 km) of track between Goffstown and Henniker Junction were abandoned in 1937 due in part to damage from the floods of 1936, declining passenger counts and few freight customers. The remaining 8.1 miles (13.0 km) from Goffstown to Manchester remained in service for freight as the Goffstown Branch. Notable customers on the branch included Homgas at Grasmere, New Hampshire Doors Co. at Factory Street, and Merrimack Farmers Exchange and Kendall-Hadley Lumber in the village. In 1976 the town's landmark railroad covered bridge burned due to arson, ending service to the center of town and forcing the remaining freight trains to stop on the eastern side of the Piscataquog River. The customers marooned by the fire either had their shipments trucked in from Manchester's railroad yard, or unloaded at New Hampshire Doors and then trucked the short remaining distance. No replacement structure was ever erected in place of the covered bridge. The last two rail customers in Goffstown were Kendall-Hadley Lumber and New Hampshire Doors Co; the former elected to truck its shipments from Manchester's railroad yard, while the latter shut down completely in 1980. The final freight train, led by Boston & Maine EMD GP7 1557, traveled to Goffstown on September 20, 1980, and the line was officially abandoned in February 1981, with the rails being removed in the following years.[5] In the dawning years of the 21st century, town and local organizations cooperated in a rails-to-trails effort, converting the railbeds into bicycling and walking trails.

On a ridge currently overlooking the Piscataquog River from the south above the midpoint between Glen Lake and Namaske Lake, adjacent to New Hampshire Route 114, originally stood the Poor Farm. In 1849 Noyes Poor sold the property to the county and it became the Hillsborough County Farm, a home for the indigent, ill, and infirm. The farm was sold into private hands in 1867 but re-acquired by the county in 1893 and again served as a residence for disadvantaged citizens of the county until 1924. A cemetery with numbered headstones is presently maintained by the county on these grounds but the tables relating the markings to the recorded names of the residents who died at the Farm appear to have been lost.[6]

The County Farm grounds were converted to the New Hampshire State Prison for Women, located until 2018 at 317 Mast Road. The facility's most famous resident was the convicted murderer Pamela Smart, who was incarcerated at the Prison for Women from March 22, 1991, to March 11, 1993, when she was transferred to Bedford Hills Correctional Facility in Bedford, New York.

Geography

[edit]Goffstown is located in southern New Hampshire, in the eastern part of Hillsborough County, directly to the west of Manchester, the state's largest city. Concord, the state capital, lies 16 miles (26 km) to the north. The town center is on the Piscataquog River near the western boundary of the town, around the intersection of New Hampshire Route 13 and 114. The village of Grasmere is located in the east-central part of town, and the neighborhood of Pinardville is located in the southeastern corner of the town, essentially forming a continuous development with the adjoining city of Manchester.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Goffstown has a total area of 37.6 square miles (97.4 km2), of which 37.0 square miles (95.9 km2) are land and 0.58 square miles (1.5 km2) are water, comprising 1.57% of the town.[1] The Uncanoonuc Mountains (uhn-kuh-NOO-nuhk) are twin peaks in the southwestern part of the town. The north peak, the highest point in Goffstown, has an elevation of 1,324 feet (404 m) above sea level, and the south peak has an elevation of 1,321 feet (403 m). The town's climate is classified as a Dfa or Dfb on the Köppen climate classification charts.

Goffstown is drained by the Piscataquog River and Black Brook and lies fully within the Merrimack River watershed.[7]

Adjacent municipalities

[edit]- Dunbarton (north)

- Hooksett (northeast)

- Manchester (east)

- Bedford (south)

- New Boston (west)

- Weare (northwest)

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 1,275 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,612 | 26.4% | |

| 1810 | 2,000 | 24.1% | |

| 1820 | 2,173 | 8.7% | |

| 1830 | 2,218 | 2.1% | |

| 1840 | 2,366 | 6.7% | |

| 1850 | 2,270 | −4.1% | |

| 1860 | 1,740 | −23.3% | |

| 1870 | 1,656 | −4.8% | |

| 1880 | 1,690 | 2.1% | |

| 1890 | 1,981 | 17.2% | |

| 1900 | 2,528 | 27.6% | |

| 1910 | 2,579 | 2.0% | |

| 1920 | 2,391 | −7.3% | |

| 1930 | 3,839 | 60.6% | |

| 1940 | 4,247 | 10.6% | |

| 1950 | 5,638 | 32.8% | |

| 1960 | 7,230 | 28.2% | |

| 1970 | 9,284 | 28.4% | |

| 1980 | 11,315 | 21.9% | |

| 1990 | 14,621 | 29.2% | |

| 2000 | 16,929 | 15.8% | |

| 2010 | 17,651 | 4.3% | |

| 2020 | 18,577 | 5.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[2][8] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 17,651 people, 6,068 households, and 4,319 families residing in the town. There were 6,341 housing units, of which 273, or 4.3%, were vacant. The racial makeup of the town was 96.6% white, 0.9% African American, 0.2% Native American, 0.8% Asian, 0.03% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 0.4% some other race, and 1.2% from two or more races. 1.8% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[9]

Of the 6,068 households, 32.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.9% were headed by married couples living together, 9.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.8% were non-families. 22.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.0% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.56, and the average family size was 3.00. 2,095 town residents lived in group quarters rather than households.[9]

In the town, 19.8% of the population were under the age of 18, 15.9% were from 18 to 24, 22.8% from 25 to 44, 28.7% from 45 to 64, and 12.8% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39.0 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.3 males.[9]

For the period 2011–2015, the estimated median annual income for a household was $70,870, and the median income for a family was $86,061. Male full-time workers had a median income of $62,167 versus $45,583 for females. The per capita income for the town was $32,574. 6.2% of the population and 3.4% of families were below the poverty line. 5.1% of the population under the age of 18 and 2.8% of those 65 or older were living in poverty.[10]

Arts and culture

[edit]Goffstown is home to Apotheca Flower & Tea, a cafe, art gallery, and flower shoppe located in the former Goffstown Village Train Depot.[11] Artists both local and global exhibit and sell their work at Apotheca, and it is a frequent campaign stop for local politicians.[12][13]

The Goffstown Historical Society is located in the former Parker Depot Store in the northeastern part of town. It is open for tours on Saturdays.[14]

Recycled Percussion, a band who placed third in season 4 of America's Got Talent, are from Goffstown.[15] The band often contributes to community events in or around Goffstown.[16] YouTuber and animated film director Griffin “The” Hansen is from Goffstown [17] and filmed every episode of his shows Cartoons VS Cancer[18] and Cartoons VS COVID in his bedroom.[19]

Goffstown Giant Pumpkin Regatta

[edit]

Every October, the Goffstown Main Street Program hosts the Goffstown Giant Pumpkin Regatta (also known as the Giant Pumpkin Weigh-Off and Regatta).[20] During this two-day event, farmers from a cross New England compete in a weigh-off with their giant pumpkins on Saturday, with the winner receiving $10,000. The pumpkins are then hollowed out and sold to local businesses for use in the regatta. On Sunday, the pumpkins are placed in the Piscataquog River under Main Street and raced up and down the river.[21] Local business personnel ride inside the pumpkins, usually in costume and having decorated their pumpkins.[22] The event began in 2000 as a promotional tactic by the New Hampshire Giant Pumpkin Growers Association, and inspired a similar event in Damariscotta, Maine.[23]

Transportation

[edit]Three New Hampshire State Routes cross Goffstown:

- NH 13 connects to the town of New Boston in the west and joins NH 114 at Main Street. The two routes remain in conjunction to the center of town, where NH 13 continues north on High Street, connecting in the north to the town of Dunbarton.

- NH 114 connects to New Boston and Weare in the west following North Mast Road, joins NH 13 at the intersection of Mast, Elm, Main, and High streets, and leaves 13 on South Mast Road. At the edge of the village of Pinardville, NH 114 leaves Mast Road and turns on to its own route to the south, with NH 114A continuing into Pinardville. NH 114 connects to Bedford in the south.

- NH 114A forms the main route through the village of Pinardville, continuing along Mast Road from the point where NH 114 leaves to the south. It connects to Manchester in the east.

Law and government

[edit]

Goffstown is governed by a five-member select board elected in the March general election to serve three-year staggered terms.[24]

The United States Postal Service operates the Goffstown Post Office.[25]

Education

[edit]

Goffstown is part of School Administrative Unit 19, serving Goffstown and New Boston.

Primary and secondary

[edit]- Goffstown has one kindergarten, Glen Lake School.

- Goffstown has two first through fourth grade elementary schools, Bartlett and Maple Avenue.

- Mountain View Middle School serves Goffstown students in fifth through eighth grade, and seventh and eighth grade New Boston students.

- Ninth through twelfth grade students from Goffstown and New Boston attend Goffstown High School.

- The Villa Augustina School was an independent Catholic school founded in Goffstown in 1918. The school served children in pre-kindergarten through 8th grade. The school closed in 2014.[26] The facility was bought by a tech company but has not had anything done to it.[27]

Post-secondary

[edit]- Saint Anselm College is a Benedictine, Catholic liberal arts college. The college has received significant national media attention in recent years; the New Hampshire Institute of Politics at Saint Anselm brings hundreds of dignitaries and politicians to Goffstown annually, most notably for the New Hampshire primary presidential debates, which have been held at the college since 2004.

Notable people

[edit]- Jacob M. Appel (born 1973), writer; lived in Goffstown from 1977 to 1983[citation needed]

- Eben Bartlett (1912–1983), state representative

- Joseph A. Favazza, 11th president of Saint Anselm College

- Gordon Hall Gerould (1877–1953), philologist and folklorist of the United States

- Jennifer Militello, poet

- Rev. David L. Morril (1772–1849), U.S. senator and governor of New Hampshire

- Mary Gove Nichols (1810–1884), activist

- Sandeep Parikh (born 1980), writer, actor, director, comedian

- David Pattee (1778–1851), politician, judge

- William Carey Poland (1846–1929), classical scholar, educator, academic administrator, and former university president[28]

- Francis Regis St. John (1908–1971), director of the Brooklyn Public Library; lived in Goffstown from 1967 to 1970

See also

[edit]- 2000 Little League World Series, featuring a team from Goffstown

References

[edit]- ^ a b "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files – New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Goffstown town, Hillsborough County, New Hampshire: 2020 DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Coolidge, Austin Jacobs; Mansfield, John Brainard (1859), A History and Description of New England, General and Local, Boston: A.J. Coolidge, pp. 502–504, hdl:2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t2988td9k

- ^ New Hampshire Register, Farmer's Almanac, and Business Directory for 1898, Burlington, Vermont: Walton Register Company, 1897, p. 105, 108

- ^ "Abandonment Notices".

- ^ Bouchard, Jay (October 28, 2016). "Town's rail trail brings exposure to mysterious county cemetery". New Hampshire Sunday News. Manchester, NH. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Foster, Debra H.; Batorfalvy, Tatianna N.; Medalie, Laura (1995). Water Use in New Hampshire: An Activities Guide for Teachers. U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (DP-1): Goffstown town, Hillsborough County, New Hampshire". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (DP03): Goffstown town, Hillsborough County, New Hampshire". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ^ Apotheca Flowers Official Website.

- ^ Sylvia, Andrew. “Ashley Judd calls election ‘Life or Death’ in Goffstown Warren stop”. Manchester Ink Link. Published February 5, 2020. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- ^ Garnick, Darren. “Toying with Politics: What Can A Stuffed Animal Teach Us About the President?” New Hampshire Magazine. Published February 21, 2021. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- ^ Goffstown Historical Society Website. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- ^ Paulu, Tom (March 11, 2015). "Recycled Percussion: Their music is garbage, and fans love it".

- ^ Chaos and Kindness S3 E32 - Giving Back to Goffstown on YouTube.

- ^ Weekes, Julia. “Goffstown native's short animated film is a funny love letter to the Bedford Village Inn”. The Union Leader. Published February 25, 2023. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- ^ Cartoons VS Cancer on YouTube.

- ^ Cartoons VS COVID on YouTube.

- ^ ”Pumpkin Regatta”. Goffstown Main Street Program. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- ^ Donovan, Lineart. “On the Grand Line: The Goffstown Pumpkin Regatta”. The Dartmouth Review. Published October 20, 2022. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- ^ McIntyre, Mary and Ganley, Rick. “Radio Field Trip: Goffstown's Giant Pumpkin Boat Race”. New Hampshire Public Radio. Published October 17, 2018. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- ^ Sylvia, Andrew. “Pumpkin Regatta centerpiece of upcoming Goffstown autumn tradition”. The Union Leader. Published October 15, 2019. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- ^ Correspondent, TRAVIS R. MORIN Union Leader (December 11, 2018). "Goffstown: It's Select Board, not Board of Selectmen". UnionLeader.com. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Post Office Location – GOFFSTOWN Archived 2010-12-15 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on November 18, 2010.

- ^ Anderson, Renee (June 17, 2014). "Villa Augustina School to close after nearly 100 years". wmur.com. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ "Villa Augustina School building sold to Hudson high-tech company | New Hampshire". UnionLeader.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ "Obituary for William Carey Poland (Aged 83)". The Journal (Meriden, Connecticut). March 20, 1929. p. 9. Retrieved July 29, 2022.